(Updated: February 15, 2024)

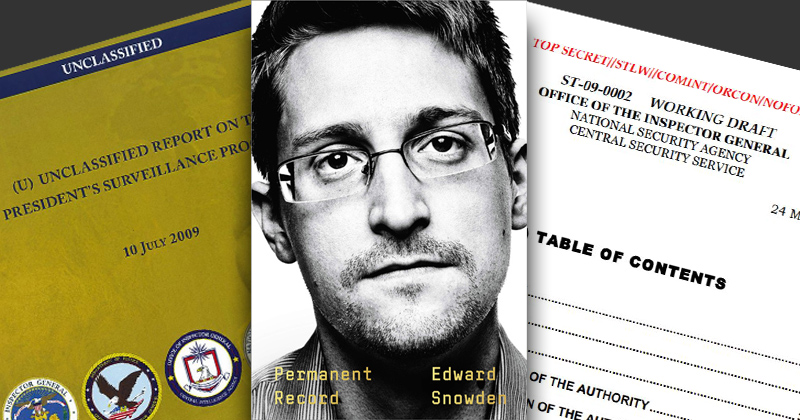

Last September, Edward Snowden published his memoir titled Permanent Record (see Part I and Part II of my extensive review). According to this book, he had one of his "atomic moments" when he read a highly classified report about the controversial NSA program codenamed STELLARWIND, somewhere in 2009 or 2010.

But one month after the book release, during a podcast interview in October 2019, Snowden said that he found that particular report only somewhere in 2012. This discrepancy makes it worth to take a close look at the STELLARWIND program: what it was about, how it was revealed, which conspiracy theories it evoked and how it's misrepresented in Snowden's book.

- Introduction

- The first revelations about STELLARWIND

- The Inspectors General report

- Searching for the classified Stellarwind report

- Bill Binney and the Utah Data Center

- Democracy Now! and a Surveillance Teach-In

- The classified STELLARWIND report

- Snowden's revelations

- Conclusion

Introduction

STELLARWIND is the cover name and the classification compartment for what was officially called the President's Surveillance Program (PSP), which was authorized by president George W. Bush on October 4, 2001 as a response to the 9/11 Attacks.

The NSA had noticed that al-Qaeda terrorists used American networks and providers for their e-mail communications, but because this was cable-bound, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) from 1978 required a warrant from the FISA Court to intercept them. Had these communications been wireless, like previously over a satellite link, the NSA would not have been required to get a warrant.

Requesting a FISA warrant took four to six weeks, so terrorists could have changed their phone numbers and e-mail addresses well before the NSA received court approval.* To "fix" this, Bush unilaterally allowed the NSA to also track down the cable-bound communications of foreign terrorists without having to obtain a warrant. Therefore, this became also known as the Warrantless Wiretapping.

In a very controversial legal opinion by Justice Department lawyer John Yoo, the PSP was justified by the president's wartime powers according to Article Two of the US Constitution.* In practice, the program encompassed four components for collecting the following types of data ("internet" actually means e-mail communications):

|

- Telephony content - Internet content |

- Telephony metadata - Internet metadata |

It should be noted that although these data were intercepted at internet backbone cables and switching facilities inside the United States, the targets were some clearly defined groups of foreign enemies: Al-Qaeda terrorists and other targets related to Afghanistan as well as the Iraqi Intelligence services.

The first revelations about STELLARWIND

Parts of the President's Surveillance Program were first revealed by The New York Times on December 16, 2005, saying that the NSA "has monitored the international telephone calls and international e-mail messages of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people inside the United States without warrants over the past three years in an effort to track possible "dirty numbers" linked to Al Qaeda."

In a radio address the next day, president Bush admitted that the NSA was intercepting one-end foreign telephone and internet communications of people related to al-Qaeda. He called this publicly acknowledged part of STELLARWIND the Terrorist Surveillance Program (TSP), but stayed silent about the other components of the PSP, which involved the bulk collection of domestic metadata.

One of the sources for The New York Times story was former NSA employee Russell Tice, who had his security clearance revoked in May 2005 based on what the NSA called psychological concerns. In January 2006, Tice claimed that "the number of Americans subject to eavesdropping by the NSA could be in the millions if the full range of secret NSA programs is used."

Three years later, in December 2008, Newsweek revealed that Thomas Tamm, a former lawyer at the Justice Department, had also been one of the sources for The New York Times. Because Tamm wasn't "read into" the PSP he wasn't able to explain its full scope and the exact details. It seems that Newsweek was also the first to disclose the code name of this program: "Stellar Wind".

Two less-known revelations

On May 10, 2006, USA Today revealed that the NSA "has been secretly collecting the phone call records of tens of millions of Americans, using data provided by AT&T, Verizon and BellSouth", which the NSA used "to analyze calling patterns in an effort to detect terrorist activity". This was one of the STELLARWIND components that president Bush had kept secret, so a big scoop, which nonetheless got very little public attention.*

Also largely unnoticed was the surprisingly frank interview that Director of National Intelligence John McConnell gave to the El Paso Times in August 2007. He provided numbers about the targeted content collection under the PSP: "On the U.S. persons side it's 100 or less. And then the foreign side, it's in the thousands. Now there's a sense that we're doing massive data mining. In fact, what we're doing is surgical."

Snowden's narrative

In his book Permanent Record, Snowden writes about the initial revelation by The New York Times, which angered him because the paper delayed it more than a year because of pressure from the White House. (p. 245)

Snowden's book doesn't mention the USA Today article, nor the McConnell interview, probably because they didn't fit his narrative: USA Today had revealed the bulk collection of domestic phone records seven years before The Guardian did based upon Snowden's documents, while McConnell made it clear that the PSP was limited and targeted instead of the alleged domestic mass surveillance.

New legal authorities

In the beginning of 2004, two newly appointed officials at the Justice Department, Jack Goldsmith and James Comey, had become worried that the bulk collection of internet metadata might be illegal. This led to a dramatic fight with the White House, after which the various components of STELLARWIND were transferred from the president's authority to that of the FISA Court (FISC). The final presidential authorization expired on February 1, 2007.

The first transfer was of the bulk collection of internet metadata, which was henceforth based on Section 402 FISA (the Pen Register/Trap & Trace (PR/TT) provision) and first authorized as such by the FISC on July 14, 2004.

The new legal basis for the bulk collection of domestic telephone records was found in Section 215 of the Patriot Act, which was approved by the FISC on May 24, 2006. Because these two components of the STELLARWIND program were not publicly acknowledged, this happened in secret.

The parts of the program that had already been disclosed by the press and admitted by president Bush, the targeted collection of content, got a temporary authorization under FISC orders as of January 2007 and were then legalized by the Protect America Act (PAA) from August 2007, which was replaced by Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act (FAA) in July 2008.

The Inspectors General report

The FAA required the inspectors general (IG) of all five agencies that participated in the President's Surveillance Program (NSA, CIA, Defense Department, Justice Department and the Office of the Director of National Intelligence) to conduct a comprehensive review of the program.

The original and highly classified joint report of these five inspectors general is almost 750 pages long and was finished on July 10, 2009. It was eventually declassified (but with significant sections redacted) in September 2015.

A short, unclassified version of this report had already been published in July 2009:

At that time, Edward Snowden worked as a systems administrator at the NSA's Pacific Technical Center (PTC) in Japan and in Permanent Record he says that he read the unclassified report about the President's Surveillance Program in the Summer of 2009, so shortly after it came out. (p. 173)

He concluded that the new FAA extended the NSA's powers: "In addition to collecting inbound communications coming from foreign countries, the NSA now also had policy approval for the warrantless collection of outbound telephone and internet communications originating within American borders." (p. 173)

It seems that Snowden, at least at the time, didn't really understand this subject, because the expansion provided by the FAA wasn't from inbound to outbound communications, but from a few specific foreign enemies (like al-Qaeda) to a wider variety of foreign intelligence targets. As such, Section 702 FAA became the legal basis for Upstream collection and the PRISM program.

> See also: NSA's Legal Authorities

Searching for the classified Stellarwind report

Snowden read the unclassified PSP report very closely because he noticed that the program also encompassed "Other Intelligence Activities" that remained classified. This gave him the impression that graver things had been going on than just targeted interception and so he went searching for the original, classified version of the report. To his surprise he couldn't find it and so after a while he dropped the issue. (p. 174)

In Permanent Record, Snowden says that "It was only later, long after I'd forgotten about the missing IG report, that the classified version came skimming across my desktop". He doesn't share how much later, but apparently it was before he left Japan in September 2010: "After reading this classified report, I spent the next weeks, even months, in a daze. [...] that's what was going on in my head, toward the end of my stint in Japan." (p. 175 & 180)

An unexpected discrepancy

But on October 23, 2019, one month after Permanent Record was published, Snowden was interviewed in the Joe Rogan Experience podcast. There, he revealed that he found the classified report only somewhere in 2012. It turned up when he ran some "dirty word searches" to help out the Windows network systems administration team that sat next to him when he was the sole employee of the Office of Information Sharing at NSA Hawaii.

Another new detail that Snowden provided during the podcast interview is that the draft report was from someone from the office of the NSA's Inspector General who had come to Hawaii. This person then left the document on a lower-security system where its classification marking STLW popped up during the dirty word search as something that shouldn't be there.

Update:

According to Barton Gellman, Snowden found the IG report about STELLARWIND in the user account profile directory of Joseph J. Brand, then the NSA's associate director for Community Integration, Policy and Records (CIPR) and as such a member of the Director's Office. When Brand visited NSA Hawaii, his personal files were copied to a temporary local cache, which Snowden had access to.* (Joseph J. Brand's name also appeared on the STELLARWIND classification guide)

According to Barton Gellman, Snowden found the IG report about STELLARWIND in the user account profile directory of Joseph J. Brand, then the NSA's associate director for Community Integration, Policy and Records (CIPR) and as such a member of the Director's Office. When Brand visited NSA Hawaii, his personal files were copied to a temporary local cache, which Snowden had access to.* (Joseph J. Brand's name also appeared on the STELLARWIND classification guide)

A decisive moment?

The moment when Snowden found the classified Stellarwind report is of some importance because it could have incited him to download and eventually leak the NSA files to the press. On October 18, 2013, The New York Times wrote:

"Mr. Snowden said he finally decided to act when he discovered a copy of a classified 2009 inspector general's report on the N.S.A.'s warrantless wiretapping program during the Bush administration."

Many people, however, will remember another moment that Snowden claimed as a "breaking point", namely when Director of National Intelligence James Clapper was forced to lie during a Senate committee hearing on March 12, 2013, which Snowden recalled in an interview from January 23, 2014 with the German broadcaster ARD:

"I would say sort of the breaking point was seeing the Director of National Intelligence, James Clapper, directly lie on oath to Congress. There’s no saving an intelligence community that believes it can lie to the public and the legislators who need to be able to trust it and regulate its actions.

Seeing that really meant for me that there was no going back. Beyond that, it was the creeping realisation that noone else was going to do this. The public had a right to know about these programmes."

Clappers testimony is also described in Snowden's book Permanent Record, but only as an example of how the legislative branch of government fails to exercise effective oversight of the Intelligence Community. It says nothing about whether the hearing had any special impact on himself. (p. 231)

All this seems contradictory, but the memoir suggests there actually was no single decisive moment: "The most important decisions in life are never made that way [at an instant]. They're made subconsciously and only express themselves consciously once fully formed". (p. 214)

So, if discovering the STELLARWIND report, nor Clapper's testimony were the single decisive moments and it apparently was a more gradual process, then there may have been other moments or events that influenced Snowden - like the following ones:

Bill Binney and the Utah Data Center

On March 15, 2012, Wired published a piece about the Utah Data Center (UDC), written by James Bamford, a well-known author of three books about the NSA. This article includes a number of speculations and accusations which are almost identical to those expressed later on by Snowden, who presents this data center as the "corpus delicti" for his claim that the NSA wants to store all our data forever. (p. 246-247)

Bamford's article says that "the NSA has turned its surveillance apparatus on the US and its citizens" and now wants to "collect and sift through billions of email messages and phone calls, whether they originate within the country or overseas" - hence the need for the huge new data center near Bluffdale, Utah.

The 1.5 million square feet Utah Data Center near Bluffdale, Utah in June 2013

(photo: AP/Rick Bowmer - click to enlarge)

The Wired article was also the first time that Bill Binney spoke out publicly. Binney worked at the NSA for almost four decades, first as a crypto-mathematician and later as the technical director of the NSA's World Geopolitical and Military Analysis Reporting Group (also known as M Group). He was also the founder and co-director of the agency's Signals Intelligence Automation Research Center (SARC).

Binney left the NSA late 2001, disillusioned by the fact that the agency chose the TRAILBLAZER collection and analysis system instead of the more efficient and cheaper THINTHREAD, which he had helped designing. Binney critized the NSA's operations after 9/11 as unconstitutional, claiming that we are close to a "turnkey totalitarian state" - which Snowden shortened to "turnkey tyranny".

In Wired, Binney claimed that STELLARWIND was far larger than has been publicly disclosed and included not just eavesdropping on domestic phone calls, but also the inspection of domestic e-mails. Binney suspected that STELLARWIND was now simply collecting everything, including financial records. Just like Snowden, Binney saw only one method to prevent this: strong encryption.

Update:

On April 3, 2012, James Bamford came with a follow-up about the "Shady Companies With Ties to Israel Wiretap the U.S. for the NSA". He quotes former NSA employee J. Kirk Wiebe who noticed "piles of new Dell 1750 servers" being delivered for the STELLARWIND program. Bill Binney added that this was organized by Ben Gunn, a Scotsman and naturalized US citizen who had formerly worked for GCHQ and later became a senior analyst at the NSA.

According to Bamford, "the racks of Dell servers were moved to a room down the hall, behind a door with a red seal indicating only those specially cleared for the highly compartmented project could enter." But rather than by NSA employees, the equipment was put together by a half-dozen employees of a tiny, and troubled, company called Technology Development Corporation (TDC), owned by the brothers Randall and Paul Jacobson from Clarkesville, Maryland. After the set-up was finished, intelligence contractor SAIC was hired to run the operation.

Democracy Now! and a Surveillance Teach-In

One month later, on April 20, 2012, Bill Binney appeared for the first time on American national television. Together with documentary filmmaker Laura Poitras and hacktivist Jacob Appelbaum he was interviewed in Amy Goodman's news program Democracy Now! (a full transcript can be found here).

Binney again claimed that after 9/11 "all the wraps came off for NSA, and they decided to eliminate the protections on U.S. citizens and collect on domestically". He saw this as a direct violation of the constitution and various other laws and decided he could not stay at NSA anymore.

Appelbaum repeated what he said at the HOPE conference in 2010: "I feel that people like Bill need to come forward to talk about what the U.S. government is doing, so that we can make informed choices as a democracy" - which is exactly what Snowden would do: leaking documents because "the public needs to decide whether these programs and policies are right or wrong."

Binney also said that a secret interpretation of Section 215 gave the government a "license to take all the commercially held data about us" and "having that knowledge then allows them the ability to concoct all kinds of charges, if they want to target you" - an allegation that comes back almost literally in Snowden's memoir. (p. 178)

A Surveillance Teach-In

Right after the Democracy Now! interview, Binney, Poitras and Appelbaum went to the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City, where Poitras organized a Surveillance Teach-In, an event to present an "artistic and practical commentary on living in the contemporary Panopticon":

During the Teach-In, Bill Binney and Jacob Appelbaum discussed government surveillance and came up with claims like "each and everyone of us is targeted by the NSA". Appelbaum also presented a list with eight specific addresses of "possible domestic interception points" which he had received from an anonymous source.

(In June 2018, The Intercept identified eight locations in the United States where there's cable interception equipment for the NSA's FAIRVIEW program. Six of these locations appeared to be identical with those on Appelbaum's list. However, these facilities are not for spying on Americans, but for collecting communications of legitimate foreign targets)

Appelbaum then called upon anyone to infiltrate AT&T to find out whether these locations are really NSA listening posts: "taking direct, non-violent action is not a violation of the constitution". This, he said, was also important for privacy and civil liberties organizations: because of a lack of hard evidence and concrete harm it was almost impossible for them to fight NSA surveillance in court.

The actual incentive?

It's not clear whether there was a livestream of this meeting, so we don't know whether or when Snowden, who was in Hawaii at that time, was able to see it (the official video was put online on September 11, 2012). The Democracy Now! interviews must certainly have attracted his attention, while the Wired article about the Utah Data Center is explicitly mentioned in Permanent Record. (p. 246)

These three events took place just around the time that Snowden started his new job at the NSA in Hawaii by the end of March 2012. Therefore, it may have actually been those statements by Binney, Bamford and Appelbaum, rather than the classified STELLARWIND report that confirmed Snowden's vague suspicions of domestic mass surveillance.

And with his all-prevailing curiosity, their claims must have been an incentive to search for the evidence for those allegations. Providing that to the press would enable the public to "understand what’s actually happening in their names" and give civil liberties organizations standing in court: ACLU attorney Ben Wizner said that in his first conversation with Snowden, one of his first questions was "Do you have standing now?"

The classified STELLARWIND report

According to the podcast interview, it was at some moment during his job in Hawaii that Snowden found the highly classified draft report about the STELLARWIND program. It's not known whether this was before or after he started downloading NSA files, but given what has been discussed above, the report seems not that important anymore as starting point for that effort. The question is rather why it didn't stop him.

Snowden likely read this classified report as close as the unclassified version back in 2009. Doing so, the first thing he must have noticed is that the STELLARWIND program was not meant for monitoring innocent Americans. The report clearly says that it was used to track down specific groups of foreigners:

- Members of al-Qaeda and its affiliates (since October 2001)

- Targets related to Afghanistan (until January 2002)

- The Iraqi Intelligence Service (from March 2003 to March 2004)

The classified report also specifies the approximate number of selectors that had been used for targeted collection of content between October 2001 and January 2007:

- Foreign telephone numbers: 15,646

- Domestic telephone numbers: 2,612

- Foreign e-mail addresses: 19,000

- Domestic e-mail addresses: 406

Because targets located in the US (not necessarily US citizens) were extremely sensitive, each of their selectors had to be approved by the chief of the Counterterrorism product line, to ensure strict compliance with the presidential authorization.

According to the final joint Inspectors General report, the NSA IG inspected a sample of the domestic selectors in 2006 and found that 95% of them were linked to al-Qaeda or international terrorist threats inside the US. Almost all the "tippers" that the NSA sent to the FBI contained domestic selectors (phone numbers, but also some content).

The draft report says that the bulk collection of telephone records was also strictly limited to "perform call chaining and network reconstruction between known al Qaeda and al Qaeda-affiliate telephone numbers and previously unknown telephone numbers with which they had been in contact."

The final joint Inspectors General report says that in 2006, as result of the contact chaining, one of every four million metadata records were seen by analysts, who determined that it was not analytically useful to chain more than two hops from a target, even though that wasn't prohibited by the presidential authorization.

Althogether, the classified review of the STELLARWIND program shows that the NSA did filter telephone and internet backbone cables inside the US and collected a huge amount of domestic metadata, but did not use this for monitoring millions of American citizens, as many critics had assumed.*

Snowden's problems with the program

After reading the report, Snowden could have concluded that his fears about domestic mass surveillance turned out to be unfounded. But on the contrary, he hid the exculpatory evidence by leaving all the aforementioned details out of his book and even said that what he found in the report was "so deeply criminal that no government would ever allow it to be released unredacted". (p. 176)

Permanent Record says that Snowden found two things in the report which he considered evidence of illegal domestic surveillance. The first thing is that the President's Surveillance Program marked a transition "from targeted collection of communications to "bulk collection", which is the agency's euphemism for mass surveillance". (p. 176)

But that's not what happened. The NSA has always conducted bulk collection for contact chaining, although traditionally that involved foreign military communications. The real shift in 2001 was not from targeted to bulk collection, but from collection abroad to collection inside the United States - but still against foreign targets.

Section from the full report of the 5 Inspectors General about STELLARWIND

(July 10, 2009, pdf-page 30, declassified in September 2015)

A redefinition of collection?

An issue that upset Snowden even more was an alleged "redefinition" that allowed the NSA to "collect whatever communications records it wanted to, without having to get a warrant, because it could only be said to have acquired or obtained them, in the legal sense, if and when the agency "searched for and retrieved" them from its database." (p. 177-178)

But while Snowden claims that the Bush administration used this redefinition in 2004 to legitimize STELLARWIND's collection of "communications" ex post facto, the report itself says that the aforementioned theory was used as a justification only for the bulk collection of internet metadata and only until March 2004.

A few months later the collection of internet metadata was brought under FISA Court authority and based upon Section 402 FISA (PR/TT). Nothing supports the idea that this definition was used as a trick to turn the NSA into "an eternal law-enforcement agency" able "to retain as much data as it could for as long as it could - for perpetuity" as Snowden wildly speculates. (p. 178)

The NSA's original privacy rules, the 1980 US Signals Intelligence Directive 18, defined "collection" as the "intentional tasking and/or selection" of specific communications, but as Timothy Edgar noted in his book Beyond Snowden: "Even if data are not "collected" under the agency's internal definition, that does not mean the agency may violate federal laws or the Constitution." The redefinition theory is already found in a piece by James Bamford from March 21, 2012.

Unprotected phone records

For the bulk collection of telephone metadata the legal situation was different, but this is also misrepresented in Snowden's book. To justify this collection, the NSA didn't need a sneaky definition, because in 1979 the Supreme Court had ruled that telephone records provided to a telecom provider are not protected under the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution. The FISA Court also applied this to metadata collected in bulk.*

In his memoir, however, Snowden made it seem like it was the NSA's own interpretation that the Fourth Amendment didn't apply to telephone metadata,* but in the Joe Rogan podcast he explained it correct, saying that "the scandal isn't how they're breaking the law, the scandal is that they don't have to break the law" - basically admitting that the NSA's bulk collection of phone records wasn't illegal.

The STELLARWIND report didn't confront Snowden with something clear and outright illegal (despite saying so in Permanent Record), but with legal interpretations he didn't agree with and which he thought the public should know about. Anyone may disagree with certain policies and legal interpretations, but that's not something covered by whistleblower protection laws.

Snowden's revelations

Even though the STELLARWIND report didn't show significant abuses, one can argue that leaking it to the press was in the public interest because it revealed the true scope of the NSA's most controversial program. But wasn't that enough? Why did Snowden continued downloading classified files? What could they reveal more than one of the NSA's most sensitive and highly classified documents?

His memoir says: "It wouldn't be enough, after all, to merely reveal a particular abuse or set of abuses, which the agency could stop (or pretend to stop) while preserving the rest of the shadowy apparatus intact. Instead, I was resolved to bring to light a single, all-encompassing fact: that my government had developed and deployed a global system of mass surveillance without the knowledge or consent of its citizenry". (p. 239)

Publication of the Verizon order

Snowden's continued scraping of NSA networks actually paid off: eventually he not only found the PRISM presentation, but also the Verizon order from April 25, 2013. This appeared to be an even better catch than the STELLARWIND report, not only because it was about the current situation, but maybe also because it contained less "inconvenient" facts.

And indeed, the very first story of the Snowden-leaks was not about STELLARWIND, but about the Verizon order. It was published by The Guardian on June 5, 2013 and revealed the Section 215 program, which this time generated a lot more attention than when USA Today first wrote about this program back in 2006.

Section 215 became the most controversial part of the Snowden revelations and was therefore replaced in 2015 by the USA FREEDOM Act, under which the NSA cannot collect domestic metadata in bulk anymore, but has to request these from the telecommunication providers based upon a warrant from the FISA Court.

Publication of the STELLARWIND report

Some three weeks later, on June 27, 2013, The Guardian published the STELLARWIND report. The accompanying article, however, was only about the NSA's collection of domestic internet metadata, probably because this was the only part of the President's Surveillance Program that hadn't been reported on before.

The Guardian said nothing about how the report debunked the fears for massive domestic surveillance, but focused on the fact that bulk collection of internet metadata had continued under Obama and eventually had been ended in 2011.

Along with the STELLARWIND report, The Guardian published a 2007 memorandum from the Justice Department, which revealed that American's metadata (both telephone and internet) may still be subject of database queries when these metadata have already been collected (through collection systems abroad for example). This is based upon the rather controversial theory that because such metadata have already been lawfully collected, there's no actual interception and therefore no breach of applicable laws.

Conclusion

Ever since the NSA illegally assisted the FBI in monitoring subversive Americans and civil liberties organizations in the 1950s and 1960s, there have been people who assumed or were convinced that CIA and NSA continued to spy on American citizens, despite the strict separation between foreign intelligence and domestic surveillance imposed by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) from 1978.

The idea of CIA and NSA as all powerful enemies of the people became a conspiracy theory which Hollywood gratefully made use of. It got a new impulse in 2006, when Russell Tice claimed that the NSA could be eavesdropping on millions of Americans and Mark Klein revealed that there was interception equipment inside the AT&T switching facility in San Francisco.

Six years later, James Bamford presented the Utah Data Center as "fresh evidence" that the NSA was now spying inside the United States while Bill Binney turned the STELLARWIND program into something like the sum of all fears by suggesting that it collected almost everything. Jacob Appelbaum urged insiders to leak classified information about these programs to the public.

And that became the mission of NSA contractor Edward Snowden: providing the press with as much information about the NSA's collection efforts as possible so the general public could decide whether it was right or wrong - an unprecedented action that could only be justified when these files would indeed reveal clear evidence of illegal activities and massive abuses.

But that was hardly the case and therefore Snowden seems to have had no choice but to continue and uphold the narrative of people like Tice, Binney and Bamford, which is that the NSA was unconstitutionally monitoring millions of Americans. However, one of his luckiest finds, the highly classified STELLARWIND report, actually debunks that story, which explains why its content is misrepresented in Permanent Record.

Links & sources

- Emptywheel: Stellar Wind IG Report, Working Thread (2015)

- Ars Technica: What the Ashcroft “Hospital Showdown” on NSA spying was all about (2013)

- The Guardian: NSA collected US email records in bulk for more than two years under Obama (2013)

- The Washington Post: U.S. surveillance architecture includes collection of revealing Internet, phone metadata (2013)

- Wired: The NSA Is Building the Country's Biggest Spy Center (Watch What You Say) (2012)

- NSA: STELLARWIND Classification Guide (2009)

- The NSA's STELLARWIND Classification Guide (2009)

- USA Today: NSA has massive database of American's phone calls (2006)

- The New York Times: Bush Lets U.S. Spy on Callers Without Courts (2005)